Longford Village History

Longford

A sense of quiet permanence, by L.H. Meakin

This is an article reflecting how village life was in 1971 and is well worth a read. Click the button below to download it.

Pupils at Longford CE Primary School (above) as it enters the new Millennium and (right) the school's pupils of bygone days, and (far right) pupils celebrating the Queen's coronation back in 1953.

Derby Evening Telegraph, Thursday 22nd June 2000

Thanks to Joanne Rowarth

Pigot's Directory of 1835 observed that "the country around here presents many agreeable prospects, and the ancient and spacious mansion of Longford Hall and its pleasant grounds are ornaments to the scenery"

Longford Conservation Area

Longford Conservation Area is predominately a rural area located in the south-east of the Derbyshire Dales District within the parish of Longford. The southern and eastern boundaries of the parish, border with South Derbyshire and the boundary extends north as far as Rodsley and Hollington. To the east and south of the parish are the villages of Thurvaston and Sutton on the Hill and to the west is Alkmonton.

Longford Conservation Area is concentrated within the parish, on land and buildings to the north and south sides of Long Lane, the latter on an east-west alignment between Alkmonton and Thurvaston. On the northern side of Long Lane is St Chad's Church, Longford Hall Farm, South Park Lodge, the Cemetery and land associated with the Longford Estate. To the southern side of Long Lane, the Conservation Area extends to include land and buildings to either side of Main Street and along Sepycoe Lane. Properties and land to both sides of Longford Lane, including parts of the former settlement of Bupton, are also included. The Conservation Area includes the majority of the village settlement.

The designation of Longford Conservation Area was in September 2011. It comprises 64.59 hectares

Historic Assets

Within Longford Conservation Area there are circa 70 properties. There are 18 buildings or structures given national recognition by being included on the 'List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest' i.e. 'listed buildings'. Buildings are 'listed' by English Heritage in conjunction with the Department of Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport.

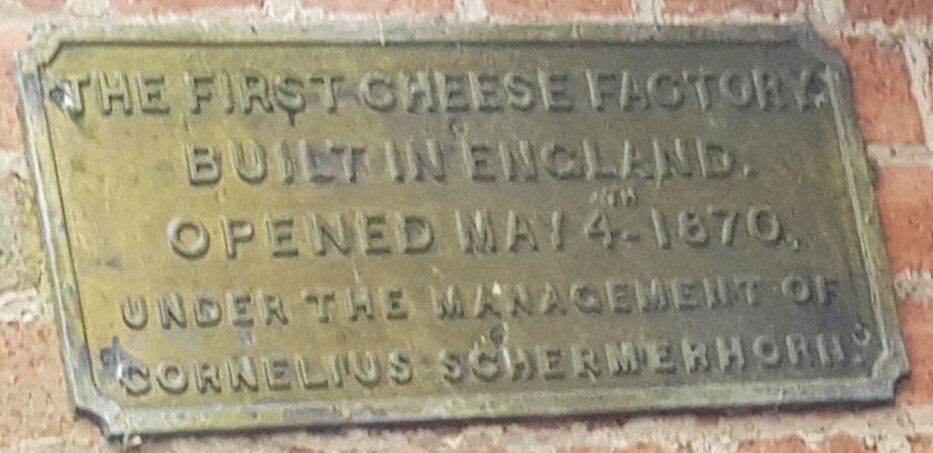

Of these 18 entries, one is listed Grade I which is the Church of St. Chad. Longford Hall, its associated gate and gate piers, Longford Hall Stables & Coach House, and Longford Hall Farm Barn (1760) are all listed Grade II* and the remaining 13 are listed Grade II. Structures range from the Cheese Factory, to bridges, table tombs and cowsheds, All are recognised for the contribution they make both individually and visually within the street-scene or surrounding landscape.

Longford Conservation Area contains no Scheduled Monuments.

Longford Conservation Area Character Appraisal

In 2007 Longford Parish Council approached Derbyshire Dales District Council in respect of consideration being given to Longford as a potential Conservation Area. The Parish Council also submitted a draft document to Derbyshire Dales District Council entitled "Longford - Proposal for Conservation Status" which included a 'Study Area' for consideration.

An initial consideration of the Study Area was undertaken by the District Council in early 2010. Whilst it was recognised that Longford had undergone a number of changes to land and buildings within the settlement and contained a relatively high percentage of 20th century properties, there still appeared to be sufficient historic and architectural features within the area for potential Conservation Area designation. A more comprehensive assessment was then undertaken which formed a Draft Character Appraisal document.

The purpose of undertaking a comprehensive Appraisal for Longford was to more clearly identify and define those elements which comprise the special historic and architectural qualities of the area and which might enable Longford to be considered for designation as a Conservation Area. The Character Appraisal considered the origins of the area, its archaeological significance, the architectural and historic quality of the buildings, the relationship of buildings and spaces, the landscape and setting of the conservation area, the negative and neutral factors affecting the area and its general condition. The document also included policy and legislative guidance and a recommendation for a potential Conservation Area boundary.

The Longford Conservation Area Character Appraisal will act as a guide for owners and occupiers of buildings within the area and for the local planning authority, as well as potential developers, interested groups and individuals. The approved document will be a material consideration when determining applications for development, dealing with appeals or proposing works for the preservation or enhancement of the area. It broadly follows the model set out in English Heritage guidance (Guidance on Conservation Area Appraisals - February 2006).

Buildings at Risk

Of the listed entries within Longford Conservation Area, three are recognised by the District Council as being at some degree of 'risk'. Longford Stables and Coach House at Longford Hall Farm (Grade II*) is included on the national 'Heritage at Risk' Register produced and maintained by English Heritage. This building, the adjacent Grade II* listed barn (1760) and Longford Almshouses (Grade II) are on the District Councils 'Building at Risk Register. Buildings on this Register are regularly monitored.

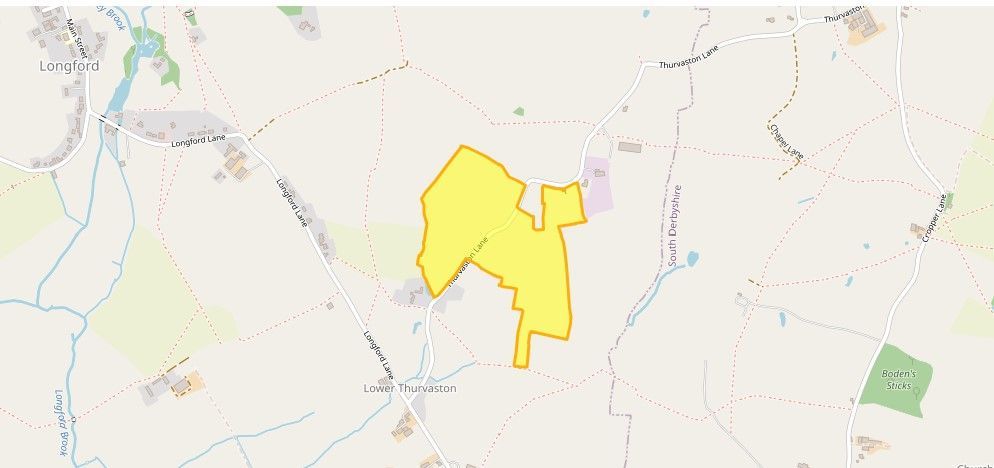

Lower Thurvaston: Medieval Settlement and Open Field System

The monument includes the earthwork and buried remains of the abandoned areas of Lower Thurvaston medieval settlement and part of the open field system. The monument is situated on a south facing slope which runs down towards the currently inhabited area of Lower Thurvaston.

Lower Thurvaston is first mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. At this time the village was in the possession of Henry de Ferieres, the lord of Longueville in Normandy, who was the largest landholder in Derbyshire. Elfin, an Englishman, held the manor for the lord. The village was called Torverdestune and is listed in the Domesday Book with Budedune (now known as Bupton) where they were valued at twenty shillings. It is recorded that there was enough agricultural land for one plough team (eight oxen) , twenty acres of meadow and a little underwood. A sunken road runs north east to south west through the monument and forms the focus of the settlement remains. The road (Thurvaston Lane) serves as the main communication link between Thurvaston and Lower Thurvaston. The position of the settlement remains along the east and west sides of the road indicates that it was linear in design. This pattern is reflected in the layout of the currently inhabited area of the village to the south of the monument.

At the northern end of the monument and to the west of the sunken road is a large terraced platform measuring approximately 100m north east to south west and 50m north west to south east. The platform is subdivided by ditches into four enclosures measuring approximately 50m by 25m. The dividing ditches are 10m wide and survive to a depth of 0.5m. Abutting the terrace on its northern edge and running north west from Thurvaston Lane across the monument is a second sunken track. The trackway survives to a depth of approximately 1m and is lined by hedqerows. The trackway follows the line of the modern field boundary and continues to the north western edge of the monument.

The curve of the field boundary in the shape of an elongated reverse 'S' is a common feature of boundaries which follow the line of medieval ridge and furrow. Clearly defined ridge and furrow running north south survives to the south of the sunken track and adjacent to the platform. To the west and north of the scheduling the ridge and furrow runs east west and is visible only as soil marks on aerial photographs. It would appear that the second sunken track formed a back lane which provided access to these fields. Approximately 100m to the south of the platform and adjacent to Thurvaston Lane are two large rectangular features. The northernmost example is sunken, measuring approximately 20m by 26m, and is situated at a kink in the road where the bank of Thurvaston Lane is less pronounced than elsewhere. It is possible it was accessible directly from the road. Post-medieval quarrying activity has disturbed this feature.

The second rectangular area measures approximately 33m by 24m. Again this is evident as a large sunken area but at its western end is a clearly defined platform measuring approximately 19m by 4m. The platform survives to a height of about 1.5m above the sunken area and is defined on its northern and western edges by a shallow gully. Its southern and eastern sides drop directly into the sunken area. The platform is interpreted as the site of a medieval building or croft, with the banks which define the platform representing the buried remains of walls. To the east of Thurvaston Lane and approximately 10m south of Mount Farm is a large oval shaped sunken area. The depression, which is interpreted as a pond, survives to a depth of approximately 0.5m at its southern end and is now dry. The northern end has been dug out to recreate a pond. Approximately 10m to the south west of the pond is a large rectangular platform defined by low banks and ditches which survive to a height of 0.5m. The platform is interpreted as the site of another medieval building with the banks representing the buried remains of walls. The bank defining the southern edge of the building platform continues in an easterly direction for approximately 70m, where it forms the northern boundary of a large rectangular enclosure and eventually links to an area of ridge and furrow. Some disturbance of this bank is evident at its eastern end where parts have been levelled to allow access for farm machinery. Between the building platform and Thurvaston Lane is an irregularly shaped sunken area. This survives to a depth of 0.5m, extends to the south for approximately 80m, and contains two low mounds. Some post-medieval quarrying activity has disturbed the earthworks but the remains indicate that this was originally a sunken track possibly providing access to the building from the main village street.

The enclosure to the south east of the building platform measures approximately 65m by 35m and has a relatively flat interior. Further enclosures of similar form are evident in the field to the east of Mount Farm but here the earthworks are less clearly defined. It would appear that this area of pasture has been improved and this has resulted in the slight degradation of the earthworks. The remainder of the monument includes the well preserved remains of the medieval open field system. The surviving remains are visible as parts of seven furlongs (groups of lands or cultivation strips) marked by headlands. The cultivation strips collectively form ridge and furrow which is curved in the shape of an elongated reverse 'S'. The field remains survive to a height of 0.3m. The area of ridge and furrow to the south of Mount Farm and south of the large enclosure is interrupted by a deep, sub-triangular pond. This is now dry. In recent years it has acted as a sump for drainage from the cow shed to the north.

Map

Longford History

Longford is a village and civil parish in Derbyshire, England. The population of the civil parish as of the 2011 census was 349. It is 6 miles (10 km) from Ashbourne and 11 miles (18 km) west of Derby.

In 1872 the parish of Longford was described as having just over 1150 people and 220 dwellings. This parish took in the settlements of Alkmonton, Rodsley, Hollington and the "liberty" of Hungry Bentley. The first three were owned by the Coke family whilst the "liberty" of Hungry Bentley was in the possession of Lord Vernon.

The village is centred on Main Street (which becomes Longford Lane shortly thereafter) and has relatively few amenities, including Longford C of E Primary School (on Main Street)

The Bonnie Prince Charlie Walk

In 1745 Prince Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Severino Maria Stuart marched from Ashbourne to Derby (Bonnie Prince Charlie Walk), passing Longford on his way to overthrow King George II and reinstate his father James III on the throne. As you can see from the story below, he was persuaded to retreat back to Scotland after reaching Derby.

The Campaign

In 1745 George II was on the English throne when Bonnie Prince Charlie, now given authority by his father to act in his name, led a French-backed rebellion to take back the Stuart throne on Scottish soil. Sailing to Great Britain in an old man-of-war ship called Elizabeth that was equipped with 66 guns and a second 16 gun privateer called Doutelle, Prince Charles landed on the isle of Eriskay on 23 July 1745.

Many Highlanders still supported the Jacobite cause, both Catholic and Protestant and Prince Charles had to rely on the support of these clans loyal to the Stuarts when the French invasion fleet accompanying him was scattered by a storm.

Now nicknamed The Young Pretender, Charles Stuart made his way to Glenfinnan, where on 19 August, 1745, he raised his father’s standard officially beginning the Jacobite uprising. Declaring his father, James Edward Stuart, King James III of England (and King James VIII of Scotland), the prince’s army of Highland clans and European mercenaries marched on Edinburgh.

Jacobite Army

Recognised as the capital of Scotland since the 15th century, Edinburgh was controlled by Lord Provost Archibald Stewart who surrendered in Sept 1745 to Prince Charles’ advancing army. After defeating the British forces at the Battle of Prestonpans in East Lothian on 21 September, 1745, the emboldened but increasingly tired Jacobite army of 6,000 men made its way into England taking the town of Carlisle in November. At the beginning of December, Prince Charles’ Jacobite army reached Derbyshire, making it only a two day walk from London and with the victorious prospect of taking England’s capital. But one fateful decision was about to change the Jacobite army’s fortunes.

Instead of taking London, Bonnie Prince Charlie’s’ council persuaded him to wait for French support, prompting him to go back to Scotland and wait until the next summer. The Jacobite army retreated back north to Scotland and successfully fought the Battle of Falkirk Muir, finally settling over the Scottish border in Inverness where they stayed for two months

The Jacobite army was by now exhausted and suffering from diminishing supplies. The youngest son of King George II, the Duke of Cumberland was also close on their tail, eventually catching up with them at Culloden near Inverness on 16 April, 1746. It was to be the last battle for the ill-equipped Jacobite army and all hopes of conquering England with a new Scottish King.

The Battle Of Culloden

The Duke of Cumberland’s British forces possessed superior gunfire as well as being physically fit compared to the mentally and physically jaded Jacobite soldiers. Prince Charles also made the grave error of ignoring the advice of general Lord George Murray, and fatally chose to fight on flat, open marshy ground, exposing the Jacobite army to the British army’s artillery. Hoping that the Duke would attack first, Prince Charles, unable to see the battlefield properly behind his lines, decided to attack first

The army’s young messenger was mercilessly shot before Prince Charles could deliver the order. Even though the Jacobites broke through the bayonets line of the British, they were shot down by a second line of the Duke’s soldiers. A combination of confusion and uncoordinated attacks by the Jacobite army, charging headlong into the musket fire of Cumberland’s forces, resulted in huge losses for Prince Charles' army, exacerbated by many of its survivors fleeing the carnage. The Duke’s soldiers were merciless to wounded Jacobite soldiers, killing them on the battlefield. Its relentless pursuit of those trying to escape and being hunted down and killed earned the Duke the grisly sobriquet of ‘the Butcher’. When Prince Charles escaped from the battlefield believing that he had been betrayed, he left almost all his personal possessions behind while many of his followers were captured and some executed.

Culloden Moor is the scene of one of the bloodiest and shortest battles in history, lasting less than an hour. The Jacobite army lost 20,00 men on the moor on the 16th April 1746, compared to few fatalities on the British side. Many highlanders were killed on this day which also included mercenaries from France, Ireland as well as Englishmen, who were loyal to the Jacobite cause. The battle was seen as the end of Highland Clan culture when the English government passed laws that banned the wearing and displaying Tartan colours as a uniform. The law was finally overturned at the end of the 18th Century.